Two-Sided Markets, Trust & Tenancy Rights

This week's issue deals with the purpose of Two-Sided Marketplaces and how they've evolved.

Two-Sided Marketplaces, Trust & Tenancy Rights (3 min)

What is the purpose of a Two-Sided Marketplace and how has it evolved over time?

The main purpose of a Two-Sided Marketplace is to provide a proxy for trust that gives two unknown counter-parties the confidence to transact with each other.

Two-Sided Marketplaces have gone from neutral market makers (simply connecting supply and demand) to landlords who are now grappling with the challenge of providing their most valuable tenants (drivers who work full-time, hosts with multiple properties, etc) with tenancy rights (sick pay, benefits, etc) that society feels they are owed.

Two-Sided Marketplaces are now moving towards treating the small but most valuable portion of their supply-side of users differently and better than the rest of their users but are reticent to do too much because it's uneconomical and unfavorable to offer those same benefits and treatments to the rest of their workforce

Purpose

Two-Sided Marketplaces thrive in areas of low trust or fragmented distribution. eBay is an excellent example of a company that was able to leverage both to its advantage. Instead of having to vet and trust each individual buyer and seller of any item (each of whom you could expect to have few repeat transactions with), you could instead use your trust in eBay as a substitute. With regards to distribution, you no longer had to scour the corners of the internet to find your $600,000 limited edition Princess Diana beanie baby, they were all being bought and sold in the same place.

Evolution

eBay never faced serious societal pressure to do more for the power sellers on its platform. It was able to care out a niche as an efficient connector of supply and demand and collect the transaction fees that came along with that role in the market. However, as two-sided marketplaces have evolved into companies that increasingly look like traditional employers, calls for overtime or sick pay for the gig workers of companies like Uber, Lyft, and Doordash have increased. These companies have resisted these efforts by claiming that the main purpose of their platform is to provide supplemental income for people with surplus time or space (or surplus goods in the case of eBay).

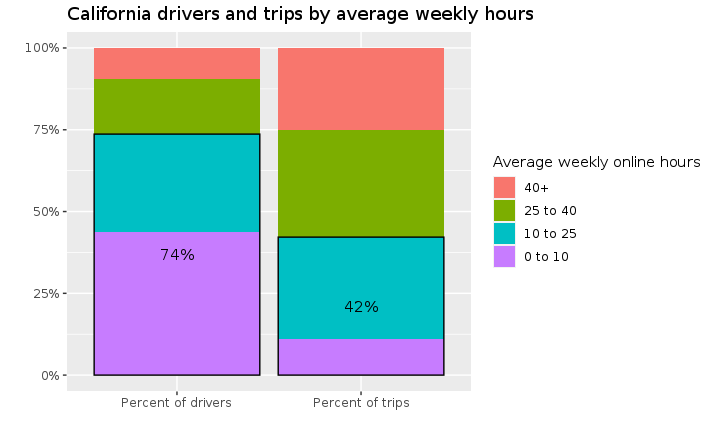

As we can see in the graphic above, the data bears out in Uber's case. There are a (relatively) small minority of drivers in California whose livelihood absolutely depends on Uber. 10% of drivers drive for more than 40 hours a week while 75% drive less than 25 hours a week.

With such a wide disparity in the number of hours worked per driver, treating every driver on its platform the same makes little sense. This is why we've slowly started to see distinctions between elements of the supply side of the gig economy. It seems difficult to argue that we shouldn't be treating these drivers (those who drive for part-time and those who drive full-time) differently but current labor laws make this difficult. So what have companies done to reward their most loyal segments of the supply side of their markets?

In the face of restrictive labor laws some companies have found a way to reward the most active users in the marketplaces. One such company was the ill-fated NYC based rideshare company, Juno. "Drivers would own restricted stock units" in Juno that could translate into cash if Juno ever went public or got sold. The shares were awarded based on how much a driver drove for Juno — as long as they hit 120 hours a month on the platform". Unfortunately, Juno wasn't able to outcompete Uber and Lyft and was later sold (and was sued by multiple groups of drivers who felt they were unfairly treated in the sale process).

In a similar manner, when Lyft IPO'd last year it actually awarded any driver who had completed 10,000 rides $1000 (ostensibly so that the drivers could buy shares with the bonus). Additionally, any driver who had completed 20,0000 trips actually received a $10,000 bonus in recognition of their efforts for the company. During Uber's IPO, they awarded drivers $100, $500, $1,000 or $10,000 for completing 2,500, 5,000, 10,000 or 20,000 lifetime trips, respectively.

While these one time bonuses were a great start, I think it's inevitable that companies such as Lyft and Uber will need to continue to offer more upside to the most active participants of their platforms both to help encourage utilization and also to as a matter of fairness.

Thanks to Charles Rubenfeld for inspiring this post with his piece on AB5 and Uber.

How satisfied were you with this week's issue?

Let me know what you think in this 3 question survey

That’s all for this week. Thanks for making it this far and I hope you found these answers as interesting to read as I found them interesting to write. If you liked what you read, feel free to like, comment, or share it with someone who you think will enjoy it.

As always,

Roosh → You